Have you ever felt like you should be able to remember something you recently learned, but can't? Do you forget most of the information you learned in a class within months after it ends?

Dr. Piotr Wozniak, creator of the software SuperMemo that was released by 1995, has spent much of his life experimenting to develop an algorithm that helps people learn the most information in the least amount of time while also letting people retain that information for a longer period after learning it (e.g. days/weeks/months/years).

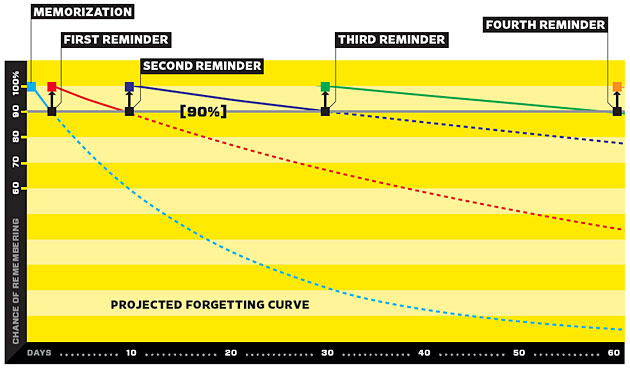

The software works by calculating the "forgetting curve", using past information about your history of correct recall among all flash cards and each specific flash card, and then predicting when you will forget that information, in an attempt to ask you again right before you forget.

By asking right before you forget (the algorithm might have calculated the next forgetting curve within days or hours), it has been shown to help you retain the information for a longer period of time after reviewing it. Asking you right before or right as you are forgetting can create a small struggle for you to remember (while still being able to actually remember), which seems to help strengthen the memory pathways in your brain.

SuperMemo's website has a fresh look now (2018-01-20) since the last time I looked at it a couple years ago, which could indicate that their software has also improved, but the SuperMemo software is known for being complicated and Windows-only. There is a more modern software that I use, which is based on SuperMemo and one of its older algorithms that is publicly posted, called Anki.

I used Anki to get As in my college courses in Calculus, Calculus II, and Linear Algebra. This list would probably be longer if I knew about Anki earlier in my life.

However, flash cards should not be your only source of studying and learning. If you try to memorize information that you would otherwise never use in your life, you may be able to consistently answer those flash cards correctly, but you may not be able to remember that information outside of flash card sessions. It also helps to memorize information that is related to information you already know. Dr. Piotr Wozniak wrote an article with helpful information on rules of learning and flashcard-making called Effective learning: Twenty rules of formulating knowledge.

Gary Wolf wrote an in-depth article on WIRED about Dr. Piotr Wozniak and his development of SuperMemo called Want to Remember Everything You'll Ever Learn? Surrender to This Algorithm.

Anki's documentation has an Introduction section that explains its purpose and differences compared to SuperMemo.

SuperMemo's main website is https://www.supermemo.com/en.

You may also be able to improve your memorization skills by using Harry Lorayne's methods in The Memory Book: The Classic Guide to Improving Your Memory at Work, at School, and at Play (1996). It is easier to remember information that is related to things we already know, for example, if you already know about history, and you are presented with a new piece of information about history that relates to your existing knowledge of history, then it will be easier to remember because it fits in and makes sense. Lorayne's methods basically allow you to create associations between completely unrelated information using a variety of systems, such as turning numbers into words, and memorizing lists of items by creating ridiculous mental images that tie those items together (for an example and explanation of some memory systems/techniques, see https://www.memory-improvement-tips.com/memory-association.html). While I still remember all of the number-sound associations for turning numbers into words from that book, I have experienced difficulty in forming a habit to use his techniques on a daily basis. This stuff should probably be taught in elementary/middle/high school to help form long-lasting habits that will stick with people for life. He also has newer books that I have not reviewed, which could be even better than the one I listed.

In Anki, I use reversible cards, and the type-answer method.

Type the answer and writing the answer on a whiteboard (or with a tablet computer): To get the type-answer method, follow this reddit answer (there's a reddit-anki community). Writing out the answer improves my ability to gauge how well I knew the answer. If I just try to think of the answer in my head and then reveal the back of the card, it's easier to fool myself into thinking I knew the answer when really maybe I was thinking between two different answers, or I didn't fully produce the answer in my head. By typing the answer or writing it on a whiteboard, I can't fool myself into thinking I knew the answer when I didn't, because my response and the true answer are clearly there for comparison (the typed answer doesn't have to be exact if you're not trying to memorize a poem or a legal definition, because then you're memorizing verbatim words instead of ideas). However, I have found it interesting when it comes to certain mathematical definitions, that I might remember the concept but forget a detail, for example wither i=1,2,3,...,k or i=1,2,3,...,infinity. At that point, it's up for you to decide based on context whether to penalize yourself for forgetting that detail (like you'll miss points if you were to get wrong on an upcoming midterm) vs letting it go (you're just trying to get a good overview of the material).

Reversible cards: To get reversible cards, follow part 2 of this tutorial. Not all cards make sense to have a reverse, for example, "how many bits are there in the key of the DES encryption algorithm?" should have the answer "64", but the reverse shouldn't say "what is 64?", because 64 can be many things besides the number of bits in the DES key, like 2^6, a Beatles song, the name of a magazine, etc (wikipedia). However, if you really want a mental cue for that reverse, it could say "what is 64 regarding the DES encryption algorithm?" as long as 64 doesn't appear anywhere else in the DES algorithm.